Jeff Hummel, MD, MPH

Medical Director, Health Care Informatics, Comagine Health

Meredith Agen, MBA

Vice President, Health Care Analytics, Comagine Health

The COVID-19 pandemic has seemed both distant and confusing to many Americans. Distant because unless one is tracking public health data, it can be difficult to see how this slow motion pandemic is progressing, and confusing because our understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on infected individuals is changing as we learn more about it each week. And it is more complicated than we initially understood.

The extraordinary effort by health care professionals to respond to COVID-19 and the impact of quarantine on patients has also meant that many other health needs such as routine immunizations and chronic illness care are going unmet. As the pandemic progresses, we need to broaden our attention to the additional impacts of deferred care. We must rely on numerous data elements to understand and articulate the importance of preventing, not only the complications of COVID-19, but also the unrelated acute care and chronic illness needs that may be overlooked or exacerbated by the pandemic. We need to creatively use data to monitor and reduce the risk of predictable non-COVID-19 conditions.

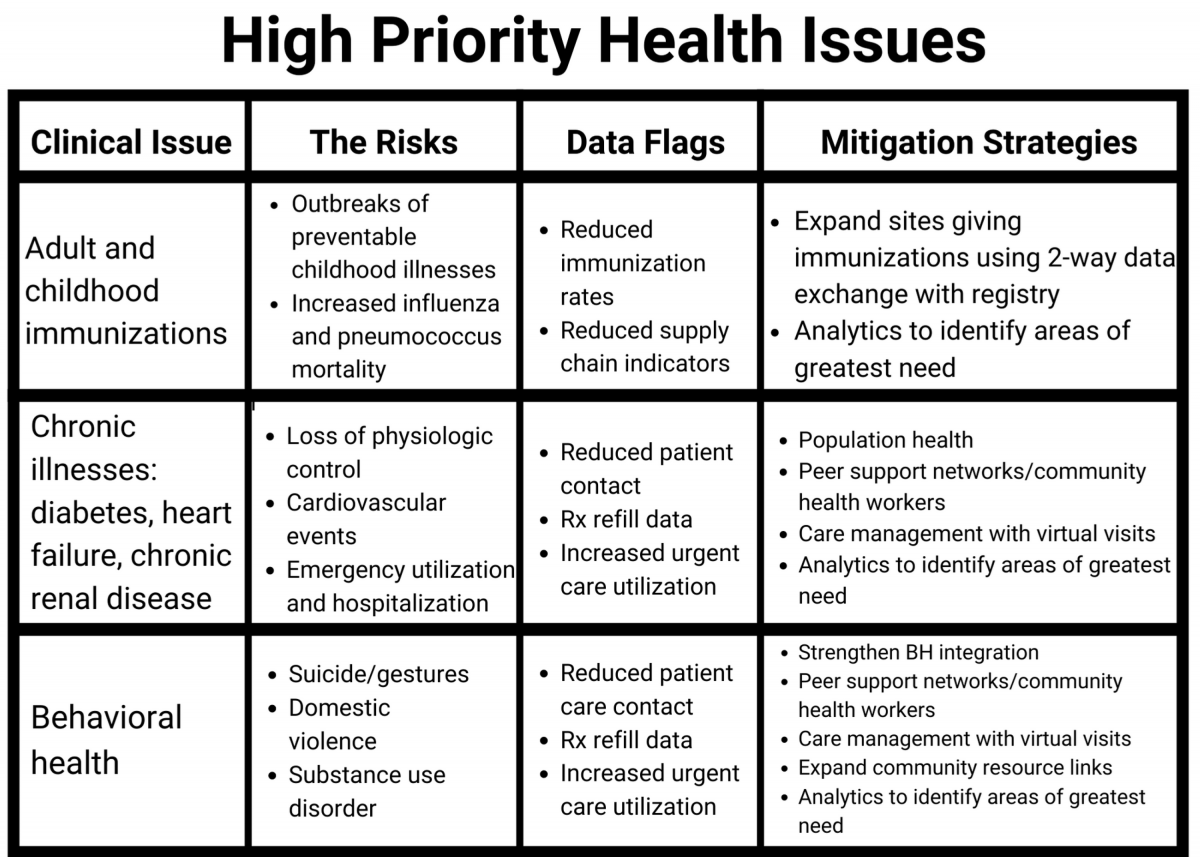

The list of non-COVID-19 health conditions that may go untreated during the pandemic is long. In addition to immunizations and chronic disease, it includes such things as behavioral health, domestic violence, pregnancy, frail elderly, substance use disorder, cancer screening and many other topics. A logical way to organize these topics is to specify for each condition what a potentially catastrophic failure would look like, what data flags we might be able to use to tell when patients are in danger and finally, determine what strategies could be put in place to mitigate the risk. The figure below shows such a framework for three such high priority health issues.

Although the types of avoidable events that are potentially catastrophic in the lives of patients will vary by health conditions, there is a clear pattern in the type of data that can be used to monitor for risk of major increases in these events. There is also a clear pattern in the strategies that can be implemented now to mitigate these risks.

Data:

- Enhance aggregation of data for population-based registries that will allow care teams to identify changes in key parameters that indicate a drop off in essential services such as immunizations, physiological parameters like glycemic control, monitoring of daily weight or simply checking in by telephone with a care manager.

- Aggregate refill data to identify situations in which at-risk populations are not refilling crucial medications according to expectation.

- Monitor when there are increases in calls for help to consulting nurses from patients experiencing worrisome symptoms.

Mitigation strategies:

- Immunization administration could be offered at places beyond physician offices and public health departments. Pharmacies already give flu shots and zoster vaccine. Immunization accessibility can be expanded to other settings while assuring strict adherence to both safety protocols and State Registry reporting requirements.

- Most chronic disease outcomes depend heavily on self-management. The effectiveness of peer support networks and community health workers in self-management support has been proven, particularly in the ability to link patients to local community resources. Funding that integrates them with clinical practice sites should be a public policy priority.

- Primary care reimbursement policy should support care management via virtual visits and remote monitoring.

- Data that can be turned into actionable, real-time information is at the core of all risk mitigation strategies.